After finishing graduate school, I briefly considered a stint in consulting and went about the interview process. One of the typically tested skills is the ability to quickly assess markets and values. A famous question in this regard is the lightbulb question: “How would you price a light bulb that never burned out?” While this product may not yet exist in the world of artificial lighting, the question as it relates to new therapeutic modalities with curative potential is equally applicable.

Seven-Figure Cures

The concept of a “cure” needs a bit of context. Treating infections is accomplished using antibiotics, and vaccinations are a common example of pre-emptive cures. The issue, as it relates to the discussion today, has a few notable differences. Firstly, the discussion relates to chronic and severe diseases. The economic models of these types of diseases rely on continuous, long term, revenue streams to support the cost of research, development, and manufacturing.

Secondly, the diseases typically discussed in this context are rather individualized (i.e. genetic disorders, specific cancers, etc). Note that this does not mean that their incidence is low; just that the curative approaches are often tailored to specific individuals. Coupling the ballooning costs of developing therapeutics with the rather specific applicable patient population has made these treatments extraordinarily expensive. Novartis’s recent claim that its SMA drug is cost effective at $4.5M, and other gene and cell therapies coming in at $500k-$1M, excluding ancillary hospital or other charges, are few examples of skyrocketing therapy costs.

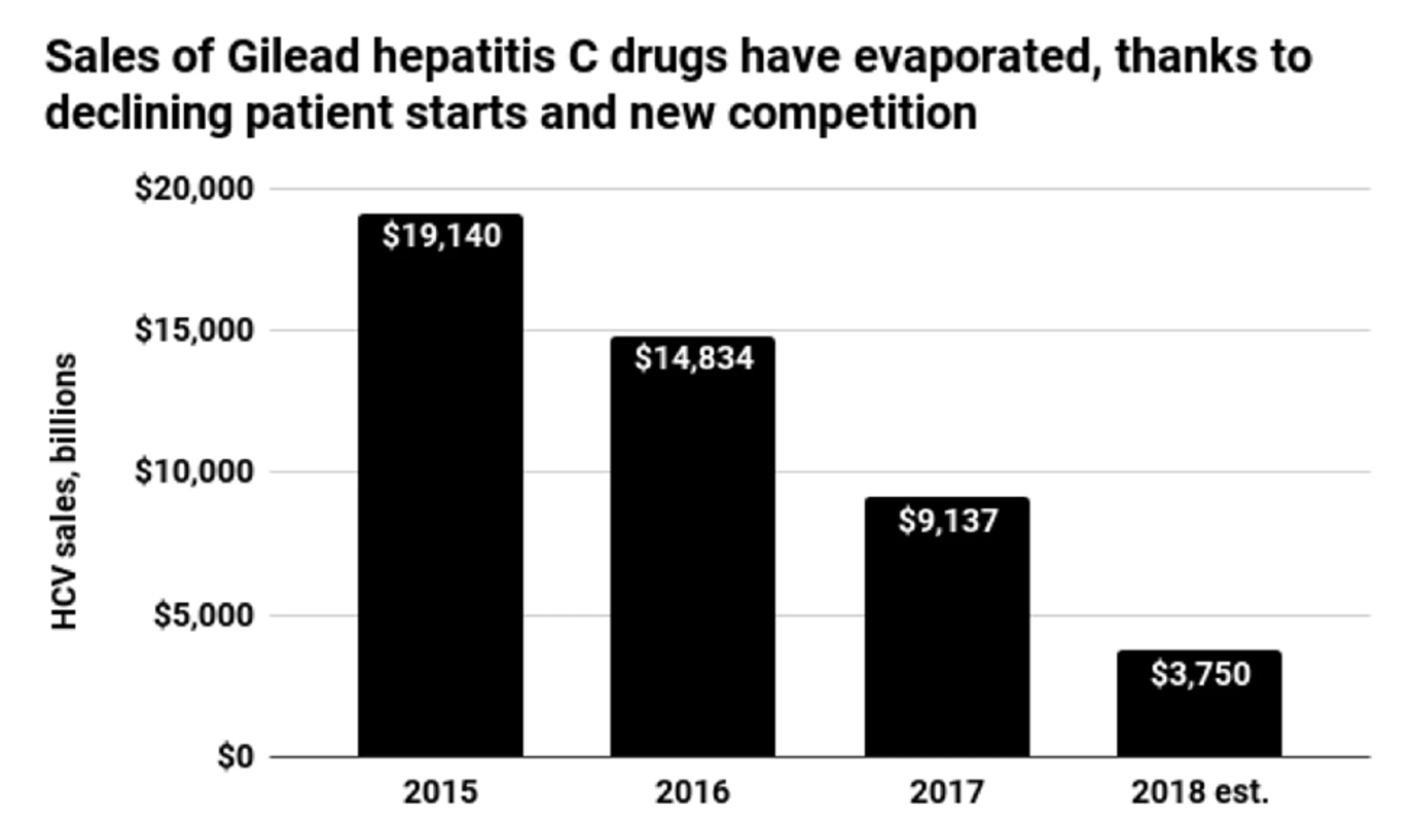

Apart from the eye-popping price tags and the accompanying ethical questions of who should foot the bill (and how to value such things), the industry faces a fundamental dilemma—is it economically viable to cure diseases? This question, as crass as it may appear, is the crux of the issue. The pharma industry is currently witnessing its implications in a more immediate fashion. Take the example of Gilead’s introduction of Sovaldi for the treatment (or cure) of Hepatitis C. Being unexpectedly effective at curing the latent prevalent population, sales skyrocketed at the outset, only to diminish to a much lower incidence rate. This impacted Gilead’s financial models and revenue projections, thus begging the question of how these drugs should be priced from a return on investment perspective.

Cell and Gene Therapies Are Designed to Cure

While the Gilead example may be a case of an unexpected cure, it was also a study in the financial dynamics of curing diseases. New therapeutics are now being designed with this express intent and associated financial models are being developed. A hallmark of these new models is the lack of recurring revenue from a continuously dosed therapeutic over an extended period of time. In such models, the aggregate projected revenues are a cumulative sum of treated patients over time and grow in a more or less cumulative linear fashion in accordance with market penetration.

These types of models assume a continuous revenue stream over time that would be used to calculate pricing metrics and net present value (NPV) assessments for each asset. An additional critical feature of this model is that therapies should continue to demonstrate efficacy to continue driving revenue over time. However, as seen in the Gilead example, this model is not sustainable if revenues do not recur. With this cautionary tale, companies developing therapies with curative potential are attempting to front-load their revenues into a single payment in anticipation of diminishing revenues in the future—leading to the extraordinary price tags that are becoming increasingly common these days.

Dealing With Healthcare Finances

These types of pricing schedules have led to increasing debates across the healthcare system. Payers are confronting extraordinary bills and considering how to manage them, notably in the context of a healthcare system where insurance policies track employment and are not standardized over the duration of a benefit period (in the case of a cure). This has begged the question of whether a single payer should bear the burden of a one-time payment that would accrue to a lifetime benefit if a patient then changes their insurance provider. It may be argued that in the broad context, this may be a wash across payers (i.e. they will receive the benefits of as many patients switching to them as they would pay out in patients switching away), but the costs are still extraordinary.

Further to this arises the question of clinical benefit and the durability of treatment. There is a relative paucity of data on the longevity of novel cell and gene therapies, and as such, relatively little effective cost to benefit analysis. Current pricing is often evaluated as a single NPV of a proposed benefit duration, but this is often a complete unknown. This has led to some companies, such as Bluebird Bio, who supports payment structures akin to a healthcare mortgage or an installment-based payment schedule that tracks the duration of clinical benefit. These models are novel and will require time and evidence to be proven as effective for the industry.

An equally important factor in clinical pricing is how developers manage their own finances. With Solvadi as a cautionary tale, the revenue models of companies aiming to cure diseases are highly diverse. The concept that revenue streams from on-market products are not cumulative, but rather follow a distribution measured by the prevalence/incidence ratio, gives rise to critical metrics around the pipeline, timing, pricing, and many other factors. A detailed analysis of this was done by the Chardan Equity Research Team (see Fig. 6-8) In their review, they identify the distributions of revenue that follow a rapid initial ascent as the prevalent population is treated, along with a sharp drop as the incident population becomes the primary market, as reflected in the Sovaldi example.

A critical aspect of company valuation under this model is determined by product timing. The development, launch, market penetration, and pipeline staging will have a significant impact on the overall continuity and growth of revenues. A crux of the model proposed by the Chardan team is that traditional models for estimating revenue and consequently company valuation can be highly variable at any future time point as a consequence of the highly divergent revenue models that are contemplated by curative diseases. To further add complications to this market mix, many companies that are currently developing curative gene therapies are working to address the same diseases (the initial low hanging fruit). As efficacy is presumed, this creates a situation where speed to market leads to a potential winner take all scenario. This means that the first successful therapy will generate revenue from the bulk of the prevalent populations, leaving only the incident market for second or third entrants. This model could effectively eliminate much of the potential revenue projections from players who are not first to market and dramatically change the economics of development. As the market is evolving, pipeline, timing, efficacy, market niche, and so forth will be the primary determinants of the economics of developers in equal measure to the reimbursement policies of payers. All of this could change over time if it is seen that, in fact, these therapies are not ultimately curative but rather have therapeutic windows that will need to be re-dosed over time to maintain efficacy. We may be considering the concept of re-dosed gene therapies as time progresses, and this will again alter the overall cost/benefit/development economics of the whole field.

Are Affordable Therapies On the Horizon?

The development of next-generation therapies that have the potential to cure significant, debilitating, and chronic diseases will transform our concept of healthcare across both clinical and financial dimensions. There is a tremendous amount to learn about the long term efficacy and value of such therapies. In addition to the structural questions, their development gives rise to a series of ethical questions about cost, access, and who can benefit from these treatments. Ultimately, this discussion is no different than any other discussion around the value of healthcare. As an industry so existentially tied to our own well being and yet still driven by fundamental economic and market realities, healthcare, including the concept of curing diseases, will ultimately be driven toward a balance of factors. As development technologies and our understanding of the models of their clinical and financial implications advance, the industry will continue to drive toward more accessible and more effective therapies that will continue to improve overall health and well being.