Shark Week is one of our favorite times of the year! Sharks are very intriguing animals due to their unique blend of beauty and ferocity, and Shark Week reminds us about their unique biology and the ongoing conservation efforts to ensure that they remain in their vital place in the ocean ecosystem.

We caught up with Dr. Toby Daly-Engel, a researcher and shark expert from the Florida Institute of Technology, to chat about her work. Dr. Daly-Engel combines genomics and marine ecology tools to study reproductive strategies in sharks. Her Shark Week special feature, Great White Shark Babies, will air on Discovery at 10:00 p.m. EDT TONIGHT (Friday, June 27, 2018).

Read on to learn more about Dr. Daly-Engel’s Shark Week show, her newly-discovered shark species, and the interdisciplinary research in her lab.

Meenakshi Prabhune: We’re so excited to talk to you about your research and your Shark Week show tonight! Could you tell us about your work covered in the show?

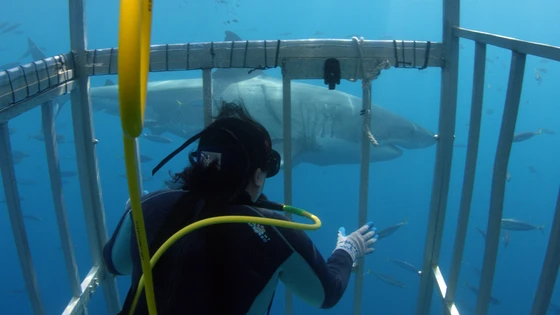

Dr. Toby Daly-Engel: I am really excited about this year’s Shark Week because not only is it the 30th anniversary but it’s also my first time participating in the show. I study evolution of reproductive strategies and ecology in sharks, and my show will particularly cover reproduction in great white sharks.

I was interested in looking at how great white shark mommas use the resources on Guadalupe Island in Mexico and where those females were giving birth. Along with studying adult sharks, we were also interested in the babies. So we also went to a lagoon in coastal Baja to collect DNA samples from baby sharks and used DNA fingerprinting methods to try and connect the two populations.

MP: Recently you discovered a new shark species; that’s so cool! Could you tell us more about this project?

TDE: In this particular project, we compared the DNA sequences of two conserved genes across closely related shark species. We realized that one particular deepwater shark that had been considered to be part of an existing species (Squalus mitsukurii) was genetically distinct and in fact a different species altogether. We named this new species Squalus clarkae, after Eugenie Clarke, a famous shark researcher.

In general, all of my research incorporates molecular methods together with ecological data that we get by physically tagging sharks. Of course, we have to be very careful when we sample live animals, as they are quite fragile. I like combining a number of different tools to approach the same question: how sharks use the ocean environment, particularly with regards to reproduction.

MP: What is the importance of genomics in shark research?

TDE: I use genomics to address every question in my experiments. Part of it is because sharks are such a conservation concern, but there is also another component to it. Sharks were the very first jawed animals on the Earth. Prior to their evolution, approximately 500 million years ago, the only animals that we know of had circular mouths. So when sharks evolved jaws, they became the first highly effective predator as they could eat things that other animals couldn't. They took advantage of these different prey sources and grew in size and diversity quickly.

Thus shark genome is sort of the first sophisticated vertebrate genome. In fact, studies have shown that their genome has a modern template and it is very similar in a lot of ways to mammals, more so than it is to other fishes. Therefore, studying shark genetics isn't just a tool for shark conservation, but it also allows us to use sharks as a really cool model for studying all sorts of other groups of animals, including humans.

MP: What are the current problems in shark conservation?

TDE: Our goal is to preserve these animals, and we do our best to get the information that we need in order to build policy. But you can't list an animal on any type of conservation policy until you have a basic understanding of its population distribution and its biology to effectively show that it needs to be protected. Right now, we're lacking a vast amount of information on most shark species, so we don't have the resources to protect them all. That’s worrisome for the future. What we know of their life history as a group indicates that they are some of the first organisms to go downhill if their ecosystem is challenged, like most top predators.

MP: There are many conservation efforts associated with sharks, but what exactly is conservation genetics?

TDE: Conservation genetics basically uses genomics tools to answer an ecological or evolutionary question that we could use to save a species. It is a pretty wide field, but here’s an example.

Say you have a river with certain types of fish in there, and then you have another river down the road with seemingly identical types of fish. One river is probably going to get dammed and you have to decide which one. In this case, you can perform genetic analysis to determine how different those species of fish are. If the fish are identical, then you can probably dam either of the rivers and have similar ecological impact. But if they've been disconnected over evolutionary time, genetics could potentially show that those two rivers have very different species of fish and damming either river could impact the inhabiting fish, perhaps even result in their extinction.

MP: What other interesting aspects of shark biology do you think people should know so that they appreciate sharks more?

TDE: The first is that sharks live really long. We now know that sharks species live and grow slowly, and that some of the species live up to 150-300 years old, potentially even longer. Also, even some of the smallest sharks species are pregnant for about two years and have very few babies at once. As sharks reproduce and grow so slowly, they don't just come back if we deplete them by overfishing, unlike some other types of fish.

Second thing is that sharks are really fragile. I wish people realized just how easy it is to kill a shark. Sharks are not mindless predators; they are very careful and are more likely to scavenge than prey, because it's low risk. You don't get to be 150 years old by being reckless. But perhaps because they're so evolutionarily old and well adapted to their environment, they are oddly fragile. In fact, researchers have found that stress response in sharks is so strong that it can kill them. Sometimes even just catching a shark on a line can kill it, even if it swims away.

MP: How does Shark Week help scientists communicate science to the public?

TDE: What's been really fun for me to participate in Shark Week is getting to talk to people about why I think sharks are neat, why I'm excited to be able to study them, and get the word out. As someone who studies an animal that is endangered in many parts of the world, I believe it's my job to speak with the media to not just educate people, but also counteract some of the media response to sharks that is less positive and educational.

MP: Shark Week featured several women researchers this year. In general, have women in shark research always had a great representation?

TDE: There's always been women interested in studying sharks, but there haven't always been women at the top positions, getting to run their own labs. That is slowly increasing, which is really great! When I started my career, I was one of very few, and certainly one of very few female professors who ran a field program. That’s because not only is shark biology potentially seen as a macho profession, but field biology with sharks is something that is not historically associated with female researchers.

We hope you enjoyed reading about Dr. Daly-Engel’s research and views on shark conservation. If you would like to learn more, you are in luck! Her Shark Week special show, Great White Shark Babies, airs on The Discovery Channel tonight (Friday, July 27, 2018) at 10:00 p.m. EDT. Don’t miss it!