There has been a fair amount of news lately regarding the decline of the pharmaceutical industry, or at least its imminent decline, on account of the vanishingly small returns on its current R&D pipelines. Much has been made of attempts to modernize, update, and reinvigorate the return on research. Significant investment has been poured into new therapeutic modalities such as gene and cell therapies. Gilead and Celgene are leading the way with 10 and 11 figure acquisitions of CAR-T therapy innovators, Juno and Kite, respectively. Other examples include Novartis’s $8.7 billion acquisition of Avexis and, to a lesser financial degree, but no less directionally impactful, GSK’s recent alliance with 23andMe.

One could easily add the mega-merger of BMS with Celgene to the list of monumental attempts to re-establish the economics of increasing returns on the continued investment in new therapeutics. In the midst of these mega dollar headlines, however, a new contender for the most innovative company has taken a lead. Without the major fanfare of mega-dollar momentum, AstraZeneca has taken the lead as the most innovative pharmaceutical company as ranked by IDEA Pharma. Its 14 places leap up from last year has been through a series of diligent brass tacks approach to fundamental science which, in combination, with a series of strategic alliances, have the potential to transform the basics of pharmaceutical R&D returns.

New Approach, Old Tricks

The approach is simple, but its implementation not nearly so. As detailed in a 2018 Nature publication, AstraZeneca’s approach takes on the core basics of research efficiency. In the simplest form, it boils down to a few basic concepts:

- Understand your target at the cellular level

- Understand the relevance at a physiological level

- Make sure your leads aren’t toxic

- Choose your patients well

- Understand your commercial market

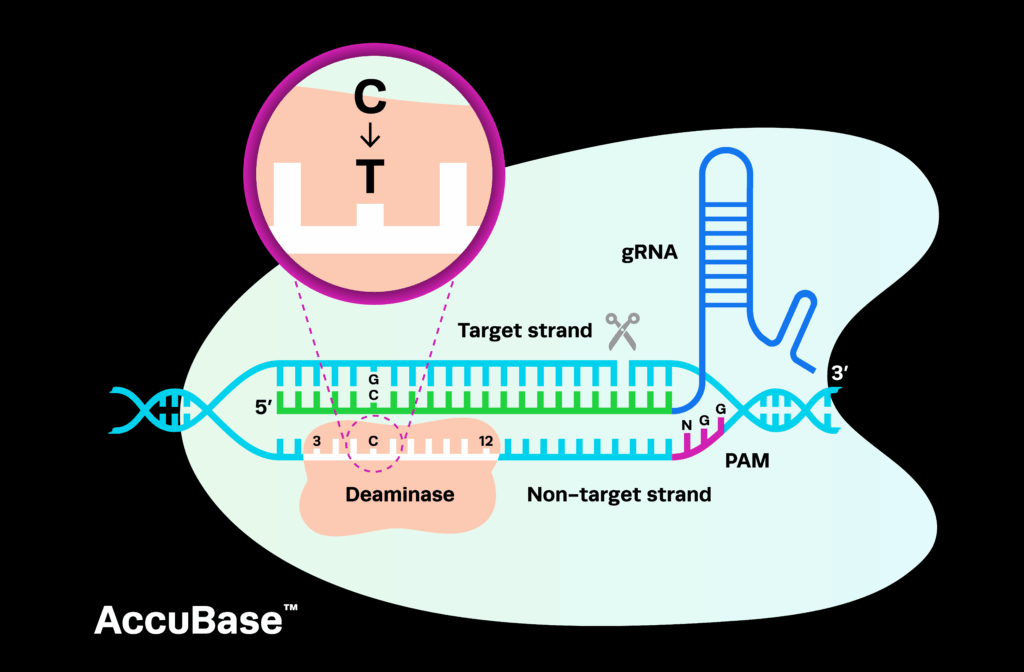

These seem like pretty basic concepts for appropriate investments, but they may be notoriously difficult to implement in the often staid infrastructures of many traditional pharmaceutical companies. However, the field is advancing rapidly with the development of technologies and capabilities that are enabling deeper insight than was previously possible. Major contributors include the development of scalable genome editing technologies, such as CRISPR, and their applications in biologically relevant cell types. CRISPR editing of stem cells and primary cells contribute a much more accurate picture of relevant biology than traditional cell lines along with the ability to develop models, reporters, and complex cellular systems at scales not previously achievable. As a first step, it has been cited that simply understanding the genetic basis of a disease can itself double the success rate of drug candidates. Combining these genetic engineering technologies with advances in 3D culture and organoid development makes research physiologically more relevant.

In addition, the convergence of iPS differentiation approaches with genetically modified cells has the potential to transform the world of toxicity assessment in a background of population genetic variation. This furthers the selection of appropriate patient study populations. Underpinning much of this development is the convergence and integration of a number of key technologies that are continually improving our ability to understand and model biological systems that more closely mimic reality. Since circa 2006-2008, genomic sequencing and iPSC reprogramming have been providing continuously improving tools for researchers to understand the genetic basis of disease and increasingly model it in biologically relevant systems. However, these capabilities have been more or less independent. Recent advances in genome editing, including CRISPR, are providing powerful tools that merge these two disciplines in exponentially powerful manners, providing for ways of writing the genetic diversity of genomics into the cellular context of stem cells. Much has yet to be seen on the impact of the convergence of technologies, but it would not be remiss to predict that these technologies will continue to enhance our understanding of biology.

For AstraZeneca, the impact of the implementation of this framework has been noticeable. As reported in Nature, the identification and optimization of lead compounds have dropped precipitously, while the focus on understanding the genetic basis of targets has increased consistently. Lack of compelling target identification data has been a primary driver of program closure before more significant investment. The number of successful projects has doubled, and while the cycle time of target ID has nearly doubled, the cycle time of lead generation has halved. The financial impact of these developments are yet to be seen, however, per the publication, investor sentiment on the buy side has tripled. What is perhaps most important, is that this is an example of a return to basics to better understand the biology that is being enabled by new and transformative technologies. In contrast to the mega-million dollar moves of other pharma companies that are swinging for the fences, this approach seeks a deeper and more measured understanding of what makes us tick. Will this strategy be more successful in the future? Time will tell.